View More: Wallace Taylor Obit | Wallace WW2 Bio | A Brief History Of Wallace & Maxine | Family Photos

The History of Wallace Taylor In WW II:

Boot Camp to Valentine’s Day, 1945 --The First 19 Months

Boot Camp to Valentine’s Day, 1945 --The First 19 Months

This biographical account was compiled and written in 2000 by cousin Greg. Over a period of several weeks, Uncle Wallace reviewed his World War II documents and photos, communicated with a handful of war buddies and did other research of which he shared all with me. During this time, I personally interviewed Wallace on several occasions in garnering information and specific details. Our personal conversations were further supported by dozens of back and forth e-mails. It was fully my privileged to step back in time with Wallace as he recalled his service in the Army Air Corp.

|

It is August 3, 1943, Wallace Taylor is going to war. He is getting there by first riding this bus that’s making its way along a not-so-smooth road in northeastern Kansas. The trip is taking place on a too hot day that began hours ago in his hometown—the small farming community of Glen Elder, Kansas. With him are 10 of the 13 other boys who graduated from Glen Elder High School nearly three months earlier. During the journey, the bus makes more stops in other small towns. Other recent graduates join them.

For months now, Wallace has known his post-graduation fate. He watched acquaintances go the same route. He read about the war in the papers, heard about it on the radio, saw it in Movie Tone newsreels, and watched it acted out in movies. Now, it is his time to join the ranks and endure the process that will take him thousands of miles from home, to combat. Finally, the bus passes through the gates at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Here, Wallace’s induction process into the U.S. Armed Services begins. Emptied from the bus like cattle, the boys hurriedly assemble. Then, herded into a nearby barracks, along with other newly arrived groups, each endures medical scrutiny. By the dozens they strip and stand naked in a row. They answer questions, take inoculations, tolerate pokes and prods, have their bodies bent and maneuvered into embarrassing angles. Privacy and pride are not at issue. |

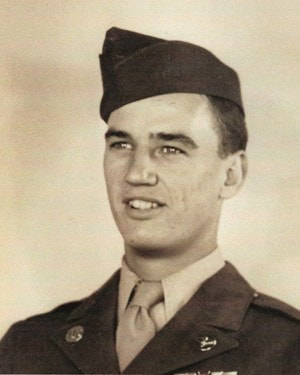

Sargent Wallace Taylor, c.1943-44

|

From one barracks to another, one event to the next, the procedure continues. They get uniforms, fill out forms, and sign papers. They drill and take orders. Luckily, they get the choice as to which military branch they would like to join.

Wallace chooses the Army Air Corps. He has dreams of flying a fighter plane, “of shooting the hell out of things,” and downing enemy aircraft. Ten days later he officially takes his oath of service and receives orders to report for basic training. He returns home to wait; life resumes as normal.

A month later, Wallace boards a bus for Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas. Though he has seen other recruits leave town on the emotional heels of family and friends, his boarding is less dramatic. The fact that his older brother is in the Army, already serving his country since 1941, has tempered his parents. There is family pride in this matter. Now, they keep a “stiff-upper lip” and wish Wallace well.

“Take care of yourself,” his father simply, yet assuredly tells him.

Wallace chooses the Army Air Corps. He has dreams of flying a fighter plane, “of shooting the hell out of things,” and downing enemy aircraft. Ten days later he officially takes his oath of service and receives orders to report for basic training. He returns home to wait; life resumes as normal.

A month later, Wallace boards a bus for Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas. Though he has seen other recruits leave town on the emotional heels of family and friends, his boarding is less dramatic. The fact that his older brother is in the Army, already serving his country since 1941, has tempered his parents. There is family pride in this matter. Now, they keep a “stiff-upper lip” and wish Wallace well.

“Take care of yourself,” his father simply, yet assuredly tells him.

Wallace, though excited, has an imprecise idea of what awaits him. He knows that in a few months he could easily be a shot at target. And, that he will shoot back—at men. Nevertheless, being of adventurous spirit, bold reputation, and young heart, he hasn’t the sense to be afraid. He keeps his excitement to himself.

After boot camp, in preparation for flight training, Wallace studies math, physics, chemistry, and other basic courses for six months at Texas Tech University. Between classes, he accumulates 10 hours of flight time in a small horse-powered plane.

Next, he is on to the Santa Anna Army Base, Santa Anna, California. The base is a “holding tank” for trainees until openings at fighter pilot schools become available. To pass time, the unit practices strict military discipline. They drill and march in formation for hours—morning, afternoon, and evening. When they don’t march they clean the base, often with toothbrushes; the grounds and buildings are spotless. A month after arriving, the men learn that additional pilots won’t be needed. They must choose another area of service in the Air Corps. Disappointed, but not discouraged, Wallace opts for Air Gunnery & Armament training.

Relocated to Lowry Field in Denver, Colorado, for the next three months, Wallace learns all phases of the gunnery and weapons systems on the B-17 Flying Fortress. His proficiency in the mechanics of gun turrets rises to the expert level. He becomes skilled at disassembling and assembling .50 caliber machine guns, even while blindfolded. He studies bomb designs and their fuses.

When not training, Wallace and his friends enjoy drives into the Rocky Mountains, trips to the Natural History Museum and local amusement park, as well as local taverns. He is in a beer-joint when it’s reported that Allied Forces have invaded France. D-Day! Jubilant, soldiers and civilians alike, yell, cheer, laugh or cry. Together, they jump up and down and raise free drinks in toast. The bars remain open long after normal closing time; it takes days for the men to get over the celebration. In the midst of it all, Wallace and the others realize that the war is continuing, and that they are going to be part of it.

After boot camp, in preparation for flight training, Wallace studies math, physics, chemistry, and other basic courses for six months at Texas Tech University. Between classes, he accumulates 10 hours of flight time in a small horse-powered plane.

Next, he is on to the Santa Anna Army Base, Santa Anna, California. The base is a “holding tank” for trainees until openings at fighter pilot schools become available. To pass time, the unit practices strict military discipline. They drill and march in formation for hours—morning, afternoon, and evening. When they don’t march they clean the base, often with toothbrushes; the grounds and buildings are spotless. A month after arriving, the men learn that additional pilots won’t be needed. They must choose another area of service in the Air Corps. Disappointed, but not discouraged, Wallace opts for Air Gunnery & Armament training.

Relocated to Lowry Field in Denver, Colorado, for the next three months, Wallace learns all phases of the gunnery and weapons systems on the B-17 Flying Fortress. His proficiency in the mechanics of gun turrets rises to the expert level. He becomes skilled at disassembling and assembling .50 caliber machine guns, even while blindfolded. He studies bomb designs and their fuses.

When not training, Wallace and his friends enjoy drives into the Rocky Mountains, trips to the Natural History Museum and local amusement park, as well as local taverns. He is in a beer-joint when it’s reported that Allied Forces have invaded France. D-Day! Jubilant, soldiers and civilians alike, yell, cheer, laugh or cry. Together, they jump up and down and raise free drinks in toast. The bars remain open long after normal closing time; it takes days for the men to get over the celebration. In the midst of it all, Wallace and the others realize that the war is continuing, and that they are going to be part of it.

After the training, Wallace departs for Kingman Air Force Base, Kingman, Arizona, and gunnery school. Here, he and the others learn to shoot a variety of weapons including .45 pistols, shotguns, “grease guns,” and the .50 calibers mounted in each Flying Fortress. Instruction on shooting fast moving targets takes place on the desert outskirts of the base. Handed a shotgun, each trainee takes his turn riding and firing from the back of a speeding pickup truck. As the truck circles the large track, blue-rock targets are thrown into the air at odd angles. This procedure simulates shooting from a flying plane. A hunter since childhood, Wallace likens the situation to pheasant hunting back home—driving the back roads, sometimes shooting through open windows.

.50 caliber machine guns soon take the place of the shotguns. Finally, the unit goes deeper into the desert to a place called Yucca Flats. True, air combat simulation begins. Positioned in salvaged B-17’s, Wallace and the rest of the young gunners sweat profusely. Each day, lumbering, smoking, and rattling into the air, the decrepit planes attain attitude in the heat-thick air. Then targets, attached to long towropes pulled by other aircraft, become the soldiers’ make believe quarry. They shoot relentlessly.

When not practicing, they seek refuge from the sun in the crawl spaces under their sauna-like barracks. Like animals hiding beneath rocks, they remain there for hours drinking water, reading books, and trying to sleep; heat exhaustion is a menacing threat.

Finally, the scorching stay at Yucca Flats ends and the weary group transfers to Avon Park, Florida. Here, Wallace and the others wait at a B-17 aircraft training area for assignment to combat flight crews. Consigned as a “waist-gunner,” he meets the people he will come to know as family during the next five months. They are: Harvey Town (Pilot), Warren Liquard (Co-Pilot), Alonzo West (Navigator), Thomas Fiore(Radio operator), Lewis McCurdy (Tail-gunner), Authur Dritz (Top-turrent-gunner), Allen Syler (Belly-gunner), and Norman Sexton (Waist-gunner) and Joseph Miller (Bombardier).

.50 caliber machine guns soon take the place of the shotguns. Finally, the unit goes deeper into the desert to a place called Yucca Flats. True, air combat simulation begins. Positioned in salvaged B-17’s, Wallace and the rest of the young gunners sweat profusely. Each day, lumbering, smoking, and rattling into the air, the decrepit planes attain attitude in the heat-thick air. Then targets, attached to long towropes pulled by other aircraft, become the soldiers’ make believe quarry. They shoot relentlessly.

When not practicing, they seek refuge from the sun in the crawl spaces under their sauna-like barracks. Like animals hiding beneath rocks, they remain there for hours drinking water, reading books, and trying to sleep; heat exhaustion is a menacing threat.

Finally, the scorching stay at Yucca Flats ends and the weary group transfers to Avon Park, Florida. Here, Wallace and the others wait at a B-17 aircraft training area for assignment to combat flight crews. Consigned as a “waist-gunner,” he meets the people he will come to know as family during the next five months. They are: Harvey Town (Pilot), Warren Liquard (Co-Pilot), Alonzo West (Navigator), Thomas Fiore(Radio operator), Lewis McCurdy (Tail-gunner), Authur Dritz (Top-turrent-gunner), Allen Syler (Belly-gunner), and Norman Sexton (Waist-gunner) and Joseph Miller (Bombardier).

|

For another three months, the newly formed team synchronizes their duties, skills, and personalities both in the air and off duty. Their training concludes with a flight to Havana, Cuba. For most, it is their first flight over a large body of water. Apprehensive, yet awed by the blue expanse beneath him, Wallace wonders what this Kansas boy has gotten himself into. Once in Havana, the crew spends the evening and night enjoying the fresh tropic air, visiting local sites, and drinking Cuban beer.

Returning to Florida, their training is complete. It is nearly Christmas; given leave, Private Taylor goes home to Kansas, his family, and girlfriend, Maxine German. Soon after the New Year, Wallace, freshly promoted to Sergeant, arrives in Savannah, Georgia. |

Maxine German & Wallace Taylor, c. 1944

|

The reality of going to Europe finalizes. The “green” crew gets a brand new, B-17. It is clean, fully equipped—ready to go to war. On January 21, 1945, after a brief checkout period, they begin their journey.

Flying north along the East Coast, their route takes them past New York City to Labrador, Canada, where they spend the night. It is -40°, and snow is over rooftops. Off the runway, they see buildings discerned only by chimney smoke rising from the white. Captain Towne selects Wallace and belly-gunner, Allen Syler for guard duty.

Flying north along the East Coast, their route takes them past New York City to Labrador, Canada, where they spend the night. It is -40°, and snow is over rooftops. Off the runway, they see buildings discerned only by chimney smoke rising from the white. Captain Towne selects Wallace and belly-gunner, Allen Syler for guard duty.

|

303rd Bomb Group Patch

|

Inside the frigid plane for hours, they become dangerously cold. Anxious for their situation, fearing for their well-being, and not knowing why or what they are guarding, they investigate the secret cargo. Stored in the bomb bays, they find blankets…piles of blankets covered by brown paper. Deciding quickly, they crawl between them. Ten blankets deep, both top and bottom, they survive on their own body heat. Though convinced they could have frozen, their harrowing night is a secret they keep.

The next day they fly to Iceland, then Ireland, and finally North Hampton, England, where they join the 303rd Bomb Group—also known as “Hell’s Angels.” They are attached to the Group’s, 359 Bomb Squadron. It has been 18 months since Wallace’s induction. Within two weeks, he will take part in his first mission over Germany. |

It is Valentine’s Day, 1945. Busy since 2 a.m. with pre-flight tasks, Wallace, along with the rest of his crew-mates, board their newly nicknamed B-17, Lucky 7. As this is Captain Towne’s first mission, joining them is Second Lieutenant Galt McClurg who will sit in the co-pilot’s seat. Experienced, McClurg has been piloting missions since September. There is less than an hour before sun-up. At his designated waist-gunner position, Wallace finalizes mechanical checkouts, assesses his gear, and connects his electrically warmed flight suit to its power source.

One by one, the plane’s four engines, cough, smoke, and grumble alive. Other planes, likewise, vibrate to life around them. Each, in predetermined order, lumbers down the airstrip, accelerates and powers into the pre-dawn sky. Other bombers, already airborne, gain altitude above the English Channel. At 10,000 feet, they strategically align into a complex and growing formation. Lucky 7 takes its place in the chain. The configuration, comprised of 311 bombers from several Bomb Groups, intersperses miles apart. Though excited, a twinge of anxiousness flutters in Wallace’s stomach. The city of Dresden, nearly 700 miles away, is the target. His first mission over occupied Germany, “Operation Thunderclap” has begun.

One by one, the plane’s four engines, cough, smoke, and grumble alive. Other planes, likewise, vibrate to life around them. Each, in predetermined order, lumbers down the airstrip, accelerates and powers into the pre-dawn sky. Other bombers, already airborne, gain altitude above the English Channel. At 10,000 feet, they strategically align into a complex and growing formation. Lucky 7 takes its place in the chain. The configuration, comprised of 311 bombers from several Bomb Groups, intersperses miles apart. Though excited, a twinge of anxiousness flutters in Wallace’s stomach. The city of Dresden, nearly 700 miles away, is the target. His first mission over occupied Germany, “Operation Thunderclap” has begun.

|

As night diminishes the 303rd’s three, 12-plane squadrons climb to a cruising altitude of 22,000 feet. Wallace can easily see the crews of the other nearby bombers. The pilots try to keep their planes in tight proximity as they cross the east shore of the Channel. Mere feet separate their wing tips.

Though connected by intercom there is little talk among crew members. While dealing with awkward, first-flight nerves, they remain alert for marauding German fighters. Unseen by the bomber crews, Allied fighter escorts slide over the top of the formation. The additional security keeps a safe distance away from the sometimes trigger-happy gunners. It is often difficult for them to make clear distinction between friendly and enemy aircraft; there have been regrettable instances of mistaken identity. |

Example photo of B-17

|

As they near the Rhine River, Wallace observes anti-aircraft flak for the first time. It is sporadic and non-threatening—silent pops of black smoke. It is well below and away from them. Distantly, it is possible to see thicker concentrations of the bursts, aimed for other bomber groups. Then the flak ceases and the flight is uneventful for miles.

A German fighter, without warning, flashes past on a downward dive near the squadron. The intercom crackles with comments. Adrenaline instantly flows through the crew. Another plane zips closely into sight. Empty shell casings snap quickly out of Wallace’s machine gun. Others shoot, too. They fire only a few bursts at the target before it disappears. Another plane blurs past. For a few seconds Lucky 7’s gunners swing and fire. Their bullets chase behind the disappearing plane. Then the action is over. Anticipating another shot, the muscles in Wallace’s hands tentatively relax from the .50 caliber’s triggers. Whether the squadron’s Allied fighter guard has intimidated the German planes is unknown. The squadron soon learns their fighter escort, fuel capacity waning, is returning to England. The 303rd is now left to its own defenses.

Though they do not encounter more enemy aircraft resistance, the minutes before the Groups’ bomb “drop point” provide additional anxiousness. The results of earlier night bombings by the British RAF become visible. The attack comprised of over 800 planes dropping 1,478 tons of high explosive bombs and 1,182 tons of incendiaries has caused a massive firestorm. Intense smoke from the burning city towers in the air. Nearing Dresden, flak salvos and cannon fire become more accurate and intense.

Wallace’s heartbeat quickens as shells burst bright red closer to the planes. Bolstered by excitement and his attentiveness to the unfolding events he does not think to be afraid. Unknown to him and the rest of the crew, shrapnel from the nearest exploding flak penetrates their Fortress’ starboard fuel tanks. Lucky 7 flies on. Its bomb bay doors open. Through the intercom, someone mumbles something about a “not so nice Valentine’s gift.” Six, 500 pound bombs release and drop through the gaping hole.

Wallace feels the plane as it turns sharply and changes altitude to escape the too close German 88mm cannon fire. He glimpses the ground, but none of his thoughts examines the destruction their volatile payload is bringing to the city thousands of feet below. He is aware of flak blasts. He looks out for returning enemy aircraft. Thoughts of the amount of time it will take to return to North Hampton flicker in the back of his mind. Hundreds of miles later, he and the rest of the crew privately experience an emergent mood of comfort as their distance from Dresden lengthens. The threat of German fighters and renewed anti-aircraft fire slackens with every passing minute.

Captain Towne notices that the fuel gauges are displaying inconsistent consumption. The needles gauging the right wing tanks visibly twitch their way toward “E.” Assessing the situation, he and McClurg conclude there is insufficient fuel to fly back across the English Channel.

The far right engine, in uncanny unison with their conclusion, coughs, sputters, and dies. Abruptly the crew’s growing sense of ease falls short. The bomber looses speed and altitude. It sinks out of the comfort of the squadron’s formation. Towne assures them that the situation is under control—they will “belly-in” at a strip near Brussels. Unable to keep up, they fade farther and farther from the formation until they are alone.

Acting quickly, pilot and co-pilot transfer what little fuel remains in the right wing tank to the left tanks. The second starboard engine sputters. Its propeller feathers. Towne compensates for the uneven torque and lowers the left wing nearly 45°. The left two engines strain to keep the plane aloft. Lopsided, it flies like a buckshot-winged duck. Their descent quickens.

A German fighter, without warning, flashes past on a downward dive near the squadron. The intercom crackles with comments. Adrenaline instantly flows through the crew. Another plane zips closely into sight. Empty shell casings snap quickly out of Wallace’s machine gun. Others shoot, too. They fire only a few bursts at the target before it disappears. Another plane blurs past. For a few seconds Lucky 7’s gunners swing and fire. Their bullets chase behind the disappearing plane. Then the action is over. Anticipating another shot, the muscles in Wallace’s hands tentatively relax from the .50 caliber’s triggers. Whether the squadron’s Allied fighter guard has intimidated the German planes is unknown. The squadron soon learns their fighter escort, fuel capacity waning, is returning to England. The 303rd is now left to its own defenses.

Though they do not encounter more enemy aircraft resistance, the minutes before the Groups’ bomb “drop point” provide additional anxiousness. The results of earlier night bombings by the British RAF become visible. The attack comprised of over 800 planes dropping 1,478 tons of high explosive bombs and 1,182 tons of incendiaries has caused a massive firestorm. Intense smoke from the burning city towers in the air. Nearing Dresden, flak salvos and cannon fire become more accurate and intense.

Wallace’s heartbeat quickens as shells burst bright red closer to the planes. Bolstered by excitement and his attentiveness to the unfolding events he does not think to be afraid. Unknown to him and the rest of the crew, shrapnel from the nearest exploding flak penetrates their Fortress’ starboard fuel tanks. Lucky 7 flies on. Its bomb bay doors open. Through the intercom, someone mumbles something about a “not so nice Valentine’s gift.” Six, 500 pound bombs release and drop through the gaping hole.

Wallace feels the plane as it turns sharply and changes altitude to escape the too close German 88mm cannon fire. He glimpses the ground, but none of his thoughts examines the destruction their volatile payload is bringing to the city thousands of feet below. He is aware of flak blasts. He looks out for returning enemy aircraft. Thoughts of the amount of time it will take to return to North Hampton flicker in the back of his mind. Hundreds of miles later, he and the rest of the crew privately experience an emergent mood of comfort as their distance from Dresden lengthens. The threat of German fighters and renewed anti-aircraft fire slackens with every passing minute.

Captain Towne notices that the fuel gauges are displaying inconsistent consumption. The needles gauging the right wing tanks visibly twitch their way toward “E.” Assessing the situation, he and McClurg conclude there is insufficient fuel to fly back across the English Channel.

The far right engine, in uncanny unison with their conclusion, coughs, sputters, and dies. Abruptly the crew’s growing sense of ease falls short. The bomber looses speed and altitude. It sinks out of the comfort of the squadron’s formation. Towne assures them that the situation is under control—they will “belly-in” at a strip near Brussels. Unable to keep up, they fade farther and farther from the formation until they are alone.

Acting quickly, pilot and co-pilot transfer what little fuel remains in the right wing tank to the left tanks. The second starboard engine sputters. Its propeller feathers. Towne compensates for the uneven torque and lowers the left wing nearly 45°. The left two engines strain to keep the plane aloft. Lopsided, it flies like a buckshot-winged duck. Their descent quickens.

|

Everyone is tense and excited at the idea of crash landing. Doubly alert, Taylor and the others scan for enemy fighter planes. They know that a single, crippled bomber is an easy target if the German air force happens by. In addition, there is uncertainty as to whether or not they have crossed the Belgium / German border. The pilots are unable to locate Brussels, the landing strip, or their exact position. There is brief discussion of “going down” in occupied territory. For a moment, Taylor imagines surviving behind enemy lines and defending himself. The entire crew is nervous about the prospect. For several more miles, the plane, tilted to one side like a decrepit old man, limps westward.

As the altimeter needle moves below the 500 feet mark, Towne and McGlug resolve that any field will do for landing. Most of the terrain below them appears flat. The fuel is dangerously low. They decide to land the plane. Forewarned, the gunnery crew assumes crash positions in the radio room located near the middle of the plane. Sitting against the fuselage, three men hold themselves tightly to the backs of the three others sitting in front of them. Heads down, they brace themselves. At 300 feet above the ground, the more experienced McClurg still flies the sinking B-17 at a lopsided angle. He levels the wings—if one gouges the ground the aircraft will flip and roll. The radio operator sends a final distress message. Of the two functioning engines, one dies. Seconds later, Towne turns off the last working motor to reduce the risk of explosion or fire. Likewise, the main electrical disconnect switch is pulled. Like a lost breath, the Flying Fortress slips silently through the air. The earth comes up fast. |

Muscles are tense in the radio room. No one speaks. Some of the men take repetitious deep breaths. Wallace’s heart seemingly thumps in his throat. He knows they will all bounce around like balls in a box if the plane flips. He trusts that he will not die. Then he forgets to think. They all wait.

Barely discernible, the hull of the plane vibrates as it converges with the ground. A brushing sound, similar to a leafy limb dragged across gravel, rushes along the bottom length of the fuselage. Soft soil and countless, gallon-sized turnips diminish the force of impact. The vegetables, not yet pulled, function like ball bearings. Dirt, lots of dirt, begins to fill the radio room. Scooped up through an opened reconnaissance photo door, it funnels in. Along with the soil, white and red chunks of turnips add to the mound. The plane rattles, bumps, and skids. The rising dirt pile lifts the men toward the ceiling. Wallace’s head knocks against an iron support, cutting his scalp.

The heavy body of the B-17 stops smoothly. Eerie silence rests about the plane. In the radio room, the men sit or sprawl about on the dirt and turnip chunks. Wide-eyed, they look at one another. Not speaking, they seem to wait for something unknown to occur. After a few moments, they begin to make their way to the waist gunner’s position. Subtle and straight-faced, they inquire about each other’s well being. They are unscathed but for the notch on the top of Wallace’s head.

Barely discernible, the hull of the plane vibrates as it converges with the ground. A brushing sound, similar to a leafy limb dragged across gravel, rushes along the bottom length of the fuselage. Soft soil and countless, gallon-sized turnips diminish the force of impact. The vegetables, not yet pulled, function like ball bearings. Dirt, lots of dirt, begins to fill the radio room. Scooped up through an opened reconnaissance photo door, it funnels in. Along with the soil, white and red chunks of turnips add to the mound. The plane rattles, bumps, and skids. The rising dirt pile lifts the men toward the ceiling. Wallace’s head knocks against an iron support, cutting his scalp.

The heavy body of the B-17 stops smoothly. Eerie silence rests about the plane. In the radio room, the men sit or sprawl about on the dirt and turnip chunks. Wide-eyed, they look at one another. Not speaking, they seem to wait for something unknown to occur. After a few moments, they begin to make their way to the waist gunner’s position. Subtle and straight-faced, they inquire about each other’s well being. They are unscathed but for the notch on the top of Wallace’s head.

Original, Lucky 7, B-17 Bomber Crash Photo

Surprised, they watch dozens of old men, women, and children hollering and cheering, run toward them. They have witnessed Lucky 7’s final approach to the turnip patch from their nearby village. From the cockpit, Captain Towne shouts back to his crew to stay aboard the plane. Gunfire rattles distantly. Someone anxiously suggests manning the guns. Towne orders them not to draw weapons.

Several yards from the plane the people stop, wait, and then happily begin to move closer. Towne and McGlurg exit the plane through a cockpit window. A policeman greets them. Towne leaves with him to contact a nearby British army detachment. The uncertainty begins to dissolve. They have landed along Oak Street in Moorsel, Belgium, just beyond German lines. The crew learns that British troops have liberated the area within the past few hours.

Several yards from the plane the people stop, wait, and then happily begin to move closer. Towne and McGlurg exit the plane through a cockpit window. A policeman greets them. Towne leaves with him to contact a nearby British army detachment. The uncertainty begins to dissolve. They have landed along Oak Street in Moorsel, Belgium, just beyond German lines. The crew learns that British troops have liberated the area within the past few hours.

|

Waiting for Captain Towne to return, the men stay aboard the plane as ordered. They watch as onlookers examine the wrecked plane. Many of the villagers inquisitively touch the fuselage and the bent propellers. Others gawk at the B-17’s plexi-glass front dug into the turnip field, its .50 caliber nose guns mostly buried. They smile, laugh and try to speak with the Americans.

Though composed, the crew members, each 22 years old, become increasingly exuberant. They are pleased, that on their very first mission together, they have assuredly handled the day’s opposing events. They talk among themselves like brothers. Hurriedly, they recall details of enemy planes, machine gun fire, flak bursts, and their engines quitting. They relive the sight of their squadron leaving them behind, and visualize the awkward angled flight of their plane. They brag about McGlurg’s skillful landing as if they had all lent him a hand. Privately, Wallace briefly recognizes the fact that he is a long way from Kansas and home. That he has become better acquainted with his own mortality is an insight he keeps to himself. In the midst of youth and this Valentine’s Day’s good fortune, he revels in the moment with his newly bonded family. |

Lucky 7 Crew: Wallace Taylor, back row, far right end in front of prop

|

Briefly listed as “missing in action,” the downed men’s unknown status is short-lived. Officials at the 303rd Bomb Group headquarters receive word from Captain Towne regarding the condition and location of Lucky 7’s crew.

Seven days later, in their new B-17 nicknamed “Lucille,” Wallace, and his crew-mates take off on their second mission. Their destination target is Nuremberg, the site of one of the most devastating Allied bombings of World War II.

Seven days later, in their new B-17 nicknamed “Lucille,” Wallace, and his crew-mates take off on their second mission. Their destination target is Nuremberg, the site of one of the most devastating Allied bombings of World War II.

After returning home after the War, Wallace never stepped onto a plane again for decades... Why? In recounting that after surviving 30 bombing missions, then, upon arriving back in the US, the transport plane he arrived on skidded off the runway on a short, mountain-top air strip in Montana, and nearly plunged off the edge of mountain... having already survived one crash landing, Wallace figured he had used up all his luck. That said, I believe a part of Wallace was in his B-17 bomber, during a brief portion of every day of his life, after his last bombing mission. -- GG